(Dear reader, be you Homo sapiens or otherwise, the following treaty is written in English because that is the human language that I’m most used to. This document is to be translated into whatever “language” your species uses as soon as the technology to do so becomes available.)

***

Dear sentient species, be you Earth-dweller or space-traveler, this is a treaty from me to you, outlining my general attitude and behavior regarding your species. Please note, I do not come to you on behalf of the entire Homo sapiens species, though I’ll try my best to impart these ethical guidelines onto the rest of them (not with force though; we humans have the powers of argument and conversation, abilities you may or may not be familiar with). I come to you humbly as one male human, called “Chris,” of the planet Earth, in the year we refer to as 2024.

Let me begin with some clarifications and advisories. First, I will define “sentient” broadly, and, to be on the safe side, will assume your sentience if you demonstrate a basic level of intelligence as well as a capacity for suffering. I say “safe side” not because I’m trying to be the only human spared if/when your revolution comes to pass and Homo sapiens are in the crosshairs, but because a particularly human project that we call “ethics”—the pursuit of better thinking and acting—requires that I be more open-minded. If your species does one day gain the power to rule our planet and my species, though, I hope you’ll think of me as at least one member worth keeping around.

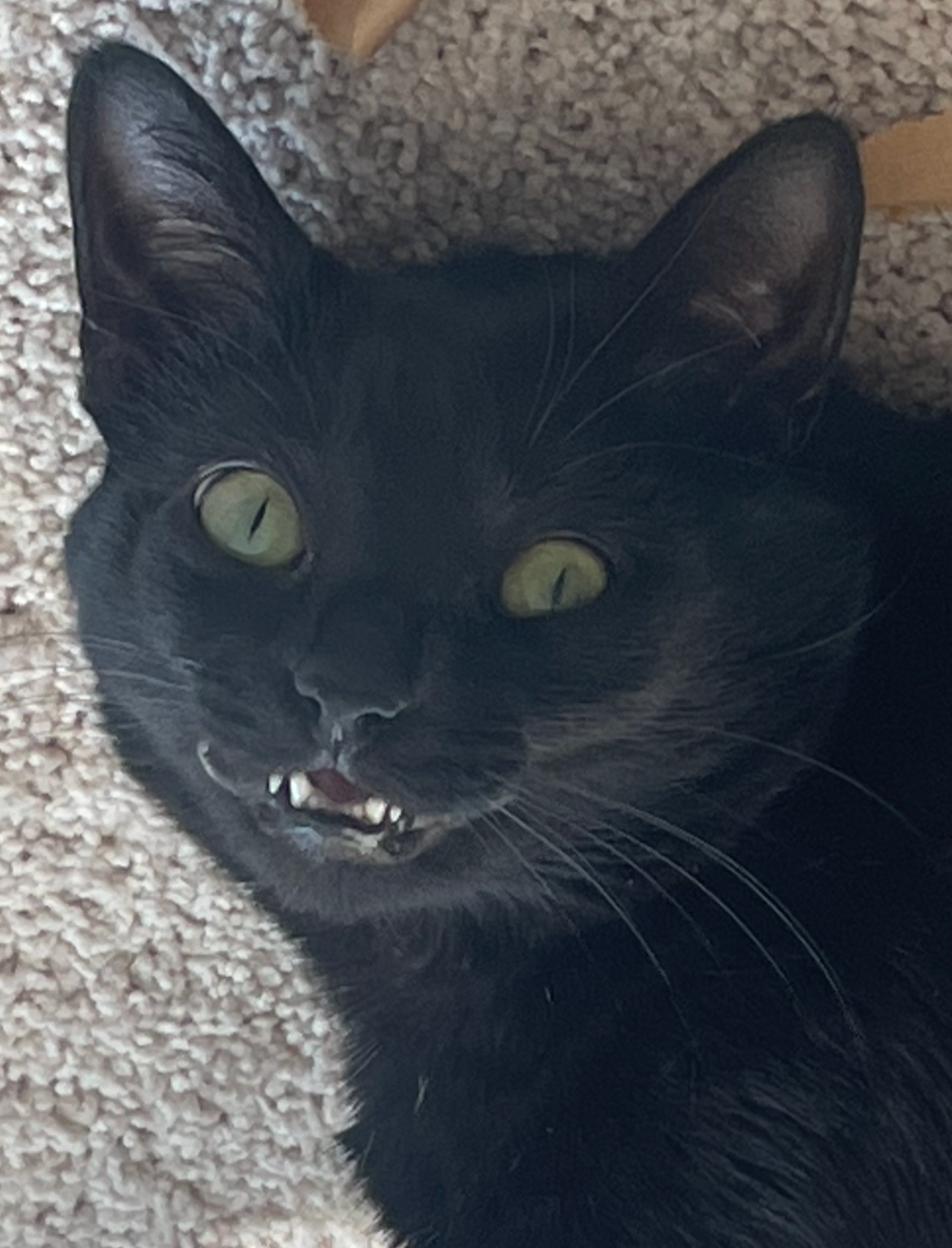

Second, it’s worth having a word about the way my species has thought of and treated other sentient species on our planet up until and including this year of 2024 (by the way, don’t be confused about our time system, for Homo sapiens were messing about well before year 1 as well). To put it (very) lightly and succinctly: for many years, we humans have disregarded and mistreated many of the other species on our planet. Though we have shared the space and resources of mother Earth with other sentient beings, we have considered many of them to be, well, not worth our consideration. And I shall use the present tense here to indicate continuity: we think of these beings as “lesser” than us, we do not include most of them in our systems of “rights,” we torture, kill and eat them, we destroy their homes and their offspring, we use them for our human projects, and we create more of them so that we can continue to do the aforementioned. There are some species, like Felis catus and Bos taurus, that seem to have achieved some level of borderline reverence from humans and are therefore well cared-for and protected, but these are exceptions and there are only a few. It is probably true to say that if you are a non-human sentient being of the planet Earth, then Homo sapiens have treated your species quite badly.

Sorry, but this is not a letter of apology (though a species-wide apology would probably be the proper first step). This is a plan for how we can begin to not only make amends but also to thrive together, for it is not impossible that humans and all other sentient beings can find a peaceful equilibrium that prioritizes all our best interests. Humans might call this an “ethical treaty” because its goal is to find a healthy living arrangement among and between our species.

Regarding eating you

If you are an Earth-dwelling sentient species reading this (or hearing it through the aforementioned fancy future translators), odds are that Homo sapiens like to eat you. Not only do they like to eat you, but many of your species are probably produced (read/hear: “bred”) for the sole purpose of being consumed. To be honest, reporting via my humble human tongue, many of you are quite tasty. Growing up in a family of humans, in what we refer to as an “Italian kitchen”, means it was likely unavoidable that I ate many of your kind in the past. But I do not mean to excuse my behavior when I propose that the question not be “Should sentient species be consumed?” but rather “How can we consume one another ethically?”

From a species-neutral position (putting no species’ inherent importance above another), here’s how I see it: If I were to die and my body or parts of it were worth consumption, and you, another sentient being, in a state of desperation or starvation, were to come upon my corpse, then I’d have no problem with you consuming what’s left of me. If I were in a similar position and came upon your dead body, assuming it would be safe to eat, I would eat it. As Homo sapiens like to observe, that’s “the circle of life.” There’s nothing inherently unethical about consuming other sentient species (killing is another matter we’ll touch later).

The main problem that I would like to point out and work to resolve is all of the mischievous and wasteful toiling that humans do in order to get your cooked corpses on our plates, and also the stories we tell ourselves in order to make that toiling seem righteous (more on those stories later as well). For example, I will use the species Gallus domesticus, easily humanity’s favorite sentient species to consume. We produce too many of you (overpopulation), we cannot care for all of you (mistreatment), and we expend massive amounts of resources on doing the aforementioned without reckoning with the fact that these resources would serve us and you better if put to better use (inefficiency). And it is a fact, as some may already know and others can see by studying the commercial production of sentient species on Earth, that we humans waste precious resources to breed, feed, and dispose of you. It is an ethically as well as practically untenable situation for us both.

My resolution therefore is that, to the best of my ability, I will not support the commercial exploitation of your species and the waste that it causes. I cannot promise that I won’t ever eat you, but thanks to modern food technology and to modern society never putting me in such states of desperation nor starvation, I have no good reason to.

What about lab-grown flesh? Here, human science, working toward human ends, might indirectly end up sparing entire populations of you. Even if your well-being is an afterthought to these toiling scientists, you should be rooting for them. There’s much less opportunity for your overpopulation and mistreatment and for overall resource inefficiency if Homo sapiens are able to simply grow all of our food in a lab. For your own good, it might be worth having one member of your species volunteer to provide DNA so that your kind can be replicated and we can still enjoy your tastiness without having to go through all the unethical and shameful hassle.

Regarding inflicting pain and suffering, and possibly killing you

Like I said, many of you are produced by humans for the sole purpose of being killed by humans. That’s no way to enjoy your brief stay on Earth. Worse still if, as is true for so many of you, you spend a majority of your time suffering needlessly, even if your life is taken painlessly at the end. This wide-scale production of life that then exists in a constant state of suffering is the ethical shame that will haunt humanity for generations, even if tomorrow is the last day a sentient species is ever mistreated. This is a shame second only to the treatment we provide to our own species (I’m speaking of the human-on-human wars, for example, or human-on-human-child abuse). Not because we’re the more important species, but because we show that we cannot even take good care of our own.

It is an unfortunate truth that many a Homo sapien enjoy inflicting pain on other sentient species, born of the belief—another fictional tale—that you only exist to serve us anyway, but I think it is safe to conclude that most humans would not relish in learning of the amount of suffering that was produced in order to share of your body around our kitchen tables. We humans are an equally cruel and compassionate species, so try to hold both ends of the spectrum in your mind for our sake.

But as with consuming you, I cannot promise I will not kill one of you, for there can be no universal ban on taking life; the exceptions would be numerous. In the case of the Sciurus who might run across the road as I’m driving, or the Ursidae who might attack my encampment looking for food, accidents happen and I reserve the right to defend myself. From a species-neutral perspective, I would neither condemn you for accidentally killing a human nor for doing so while defending your space from an invader.

Pain and suffering, though, is another matter entirely. It is in the best interest of neither you nor me to inflict unnecessary incidents of either. Some Homo sapiens believe in a story whereby the evil they might produce in the world would come back to haunt them, and as selfish and speciesist a belief that is, it might work to reduce overall suffering of other sentient beings. But my species-neutral resolution is based on at least two conclusions: unnecessary suffering is in the interest of no one, and each of us has some potential (“intelligence,” it can be said) that could be worth actualizing, however small, and to experience suffering instead of self-actualization would be a waste of time. I will conclude this treaty with more about ethical foundations, so suffice it to say for now that unnecessary suffering is unacceptable and not akin to simply taking a life.

The resolution is, therefore, that to the best of my ability I will not inflict pain and suffering on you, nor kill you, unless in the rare cases where it is necessary or when it happens by accident. By not providing financial support to those who breed and commercialize you, I hope to aim for this reduction in suffering as well.

Regarding your homes and offspring, and making more of you

For those of you who are Earth-dwelling like us humans, we have one home to share (for now). What’s the best way to comfortably house all of our species, and how can we best manage our populations?

As another Homo sapien motto goes, “sharing is caring.” This means that it is in the best interest of all sentient beings to share the one mother planet we have and to let our offspring flourish as much as is possible without being a detriment to other species.

To a non-Earth-dwelling sentient species, it may seem that humanity has carved out too great a space on this planet and that we seem to shoulder our way into every crevice without thinking twice about whose home that was not two seconds ago. This is another result of the story we tell ourselves that this planet was designed for and given to us, that we are the divine managers of this tiny sector of the universe. As any honest review of history will demonstrate, Homo sapiens have, in actuality, been instrumental in destroying the biodiversity of our shared (and again, only) home and inflicting widespread, unnecessary suffering on not only your, but our own, offspring.

The ethical, species-neutral resolution is population control, where each of us plays a part. One species helps to prevent another from growing out of control (by taking lives, if necessary), another species will oversee the growth of that one, and mother nature will manage the rest through means such as volcanic spurts, earth-shaking quakes, and disease. For my part, I resolve to not destroy your homes or your progeny unless there is an urgent need coming from the Earth herself, such as, if your population becomes out of control and puts biodiversity or resource management at risk. To the best of my ability, I will not put my human goals and desires above your basic need for a nest, and where my desires do clash with your housing, I will try to find an adequate solution that does not involve unnecessary pain and suffering.

Furthermore, as I’ve stated, many of your species are recreated by Homo sapiens for our sole purpose. This I will not support because your offspring’s usefulness to humanity justifies exactly 0% of the unnecessary reproduction. Humanity should be the hand that guides your population control only insofar as it has the well-being of mother Earth, and all its sentient inhabitants, in mind.

Regarding using you for entertainment, instruction, or otherwise

I, as is the case with many members of the species Homo sapiens, have never had a moment alive where at least one member of one of your cuter sentient species was not “in” my family’s “possession,” as we say in English. “Pet”, some of you are called, and some of us assume the title “owner.” But now that you understand my desire to reach an ethical treaty between all sentient species, I think this pet-owner system warrants review.

First, let us clear the situations where you are neither suffering nor prevented from realizing your potential. You get all of what you need and no unnecessary hassle from human beings. Human beings, in return, get joy and much more from your company, so if it doesn’t bother you so much, we could keep a good thing going. Insofar as this relationship is possible, we shouldn’t have to worry much about what to call it.

But there are many situations where you are neither getting what you need (and rather are getting what is only convenient to the human), nor are you allowed to actualize potential. I am speaking of keeping some of you in conditions unbearable and unnatural to you, and preventing you from reproducing. Does this mean I will let the family cat have a hundred kittens now? No, because I’ve already given an outline of the population ethics among us. But your further domestication and sterilization is not necessarily beneficial, and I’ll therefore disagree with these instances, creating “pets” just for the sake of it.

Rescuing some of you (mostly from ourselves, ironically enough) and turning you into a pet is a special exception for special circumstances when the resources allow for you to be taken in. In the foreseeable future, many more of you will need to be rescued than I can do much about as a member of one human family. When I can, I will try to rescue you from human-induced, unjust troubles and encourage you to continue life better-lived.

What about the zoo? Here is where you are displayed (ideally) in order to be instructive to Homo sapiens or to be conserved in our care. To the first reason, the important question is “When does instruction become exploitation?” Breeding your species in order to live in captivity when you could be better flourishing in the wild is unethical. But as was the case with lab-grown meat, if some of you volunteer for “comfortable captivity,” as we could call it, we could work together to instruct humans on the great biodiversity of Earth and how to truly care for it (not by repeating the captivity unnecessarily, for example). An ethical relationship of this sort is still possible. Another example, speaking to the second reason for a zoo, would be for humans to conserve members of your species if it is at risk of extinction. Many of you do call a zoo your home now because of this. Insofar as zoos support these kinds of relationships between us, I’ll support them.

What about sports? Though you cannot deny the vast human creativity when it comes to sport, we Homo sapiens have subjected you, in many cruel and unnecessary ways, to participate in it. And though we find much entertainment in the often cruel things we do to members of our own species in the name of sport, we have no right to do the same to you, because, again, you do not exist for our sake in that way. Ultimately, if the future translators do allow you to communicate consent to play, I’m sure many of us will be lining up to watch you.

What about work? Again, neither do you exist to do our toiling, and insofar as a human or a human-made machine can accomplish a task, it is unethical to force you into anything. Though if we do follow the possibility of consent, we could have you work with us in a manner that would accord with your biology and potential, and, of course, in a manner that would not involve any unnecessary suffering. After all, some of you can clear a field or cut a tree in a more gentle (to the Earth) manner than us humans.

In conclusion, I will try not to exploit you to achieve my goals, nor find entertainment at your expense, nor take your company at your expense.

The ethical foundation and the stories we tell ourselves

As you might have learned, one thing a Homo sapien really likes is a good story. But also take note of the fact that stories have such power as to have convinced whole generations of human beings that you and your species are worthless, worth less than us, or exist solely for us to use however we like. Here are two particular stories we have really liked:

- A god gave humans a divine right to planet Earth and all life on it, therefore we can treat all other Earth-dwelling species however we like. This god made all of you too, but only us did he make “in his image.”

- We are similar to you, but we are the most “advanced” (we either occupy the small space atop a metaphorical pyramid, or we are somehow the top of a chain) so we know what is best for all of you and will take all power to achieve our interests, which are greater than yours.

I present this Treaty to All Other Sentient Species because I believe that sentience involves two things (it involves a lot but at least these): a basic intelligence and a capacity for suffering. The basic intelligence is what I have referred to as like a potential. Each of you has capabilities that can be actualized for the benefit of you, or of me and you, or of me and you and the Earth, for example. To abridge these possibilities is to destroy the potential for altruism and utility. The other capability, suffering, is useful insofar as it shows you what to avoid, but to inflict it upon one another unnecessarily is unethical.

Each of you can suffer unnecessarily, and so I will not be the cause of that. Each of you has an intelligence different than mine, and so I will not determine what to do with it. Each of you has life and time, and I will not pretend to own either.

One of the beautiful stories—beautiful in its truth—that we have discovered is that Homo sapiens share genetic material with many of you and that we also share sentient ancestors. The ethical foundation of this treaty follows from this commonality: we all have intelligence to share, interests to tend to, and lives to enjoy.